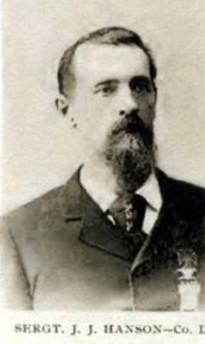

enlisted 30 Aug 1862 at age 26 as a Sergeant in Company D, 15th Infantry. He mustered in 8 Oct 1862;and mustered out 13 Aug 1863 after the Battle of Port Hudson, La. At the time of his enlistment he was residing in and credited to Newmarket. During his nine months in service, not only was he was the Company Sergeant, but a sharp-shooter who was on the front lines during the battle. At the end of his active service he joined the State militia, belonging to the Newmarket Guards (Company G), Newmarket, which was composed of fifty men—himself being Captain; Alanson C. Haines, First Lieutenant; and Andrew Randall, Second Lieutenant.

enlisted 30 Aug 1862 at age 26 as a Sergeant in Company D, 15th Infantry. He mustered in 8 Oct 1862;and mustered out 13 Aug 1863 after the Battle of Port Hudson, La. At the time of his enlistment he was residing in and credited to Newmarket. During his nine months in service, not only was he was the Company Sergeant, but a sharp-shooter who was on the front lines during the battle. At the end of his active service he joined the State militia, belonging to the Newmarket Guards (Company G), Newmarket, which was composed of fifty men—himself being Captain; Alanson C. Haines, First Lieutenant; and Andrew Randall, Second Lieutenant.

Born in Lee, NH to Robert and Lucy (French) Hanson, the family moved to Newmarket when he was a young boy. In the 1860 census he and his wife Lydia live in town and work in the cotton mills. By 1880 they had moved to Biddeford, Maine, still working in cotton mills. He was a Mason and a member of Rising Star Lodge of Newmarket as well as a member of Geo. A. Gay Post, No. 18, G. A. R..

He died 24 Dec 1899, a widower, in Manchester. His Death Notice in the 27 Dec 1899 issue of The Exeter Newsletter states:

He was the owner of a large farm in Exeter, to which he was much attached; he died in Manchester on Sunday, age 62 years. He was an overseer on the Amoskeag Corporation, much interested in politics, and a man of prominence in Manchester where he was held in high esteem by all classes.

June 11, 1869, Geo. A. Gay Post, No. 18, G. A. R., was organized and Comrade John J. Hanson was its first commander. The Post was  active up until after WWI, when its duties and responibilities were taken pover by the American Legion. A faternal organization of past Civil War veterans, the post decorated veteran graves on “Decoration Day”, aided veteran families and widows, provided a social focal point for both vetrans and the Newmarket community at large. The local chapter participated in the Civil War monument raised in City of Manchester, 1880. It also built Newmarket’s bronze memorial to commemoriate those who served during the Civil War. The post was named after Lt. George A. Gay, who was killed in action at Antietam.

active up until after WWI, when its duties and responibilities were taken pover by the American Legion. A faternal organization of past Civil War veterans, the post decorated veteran graves on “Decoration Day”, aided veteran families and widows, provided a social focal point for both vetrans and the Newmarket community at large. The local chapter participated in the Civil War monument raised in City of Manchester, 1880. It also built Newmarket’s bronze memorial to commemoriate those who served during the Civil War. The post was named after Lt. George A. Gay, who was killed in action at Antietam.

The Woman’s Relief Corps, an auxiliary of the Post, was organized October 10, 1889, with M. Augusta Rand (wife of veteran Cyrus R. Rand) having been its first president. As quoted by the Granite Monthly: “With true loyalty have these unselfish women sought to aid and assist their brothers in every worthy word and work and are a power for good in this community”. The WRC was active in the community up until the end of WW II, when the membership eventually enrolled in the American Legion Auxilliary.

In the spring of 1907, seven year’s after Hanson’s death, The G.A.R. organized a Sons of Veterans post and named it in honor of the former Sergeant “John J. Hanson Camp, Sons of Veterans”. Franklin A. Brackett voted its first commander.

An estimated 10,000 Union soldiers were killed, wounded or died from illness during siege. The Confederates suffered a loss of 750, nearly half of whom had died from sickness. The  longest siege of the Civil War came to an end with the surrender of roughly 6,500 Confederate soldiers. The grand Union strategy of the Civil War was the “Anaconda Plan” developed by Gen. Winfield Scott in 1861. By imposing a naval blockade of the Southern coastline and then retaking the Mississippi River, Scott’s plan would eventually strangle the Confederacy to death. By early 1862, the blockade was in effect and attention turned to the Mississippi River.

longest siege of the Civil War came to an end with the surrender of roughly 6,500 Confederate soldiers. The grand Union strategy of the Civil War was the “Anaconda Plan” developed by Gen. Winfield Scott in 1861. By imposing a naval blockade of the Southern coastline and then retaking the Mississippi River, Scott’s plan would eventually strangle the Confederacy to death. By early 1862, the blockade was in effect and attention turned to the Mississippi River.

(photo: illustration, firing from atop the citadel)

The Navy announced the attack with an all night bombardment of the Confederate works and then the Union infantry moved forward at 6 a.m. on May 27, 1863. The Confederates were ready; thousands of Union soldiers attacked straight into an area of deep ravines. The rugged terrain broke up the attacks and funneled the men into a position ringed on three sides by Southern troops. The assault degenerated into a blood bath.

As this fighting was underway, 30 pieces of Union artillery bombarded the Confederate earthworks on the east side of Port Hudson. The shelling was followed by an infantry attack by Brig. Gen. T.W. Sherman’s Division. Like the attack on the northern defenses, the attack on the east failed. By the end of the day, the assault was over. Thousands of Union soldiers lay dead and wounded and the victory shouts of Gardner’s Confederates echoed over the battlefield.

As this fighting was underway, 30 pieces of Union artillery bombarded the Confederate earthworks on the east side of Port Hudson. The shelling was followed by an infantry attack by Brig. Gen. T.W. Sherman’s Division. Like the attack on the northern defenses, the attack on the east failed. By the end of the day, the assault was over. Thousands of Union soldiers lay dead and wounded and the victory shouts of Gardner’s Confederates echoed over the battlefield.

(photo: Battle of Port Hudson, painted 1864)

The siege went on until July 9, 1863, when Gardner learned that Vicksburg had fallen and his courageous effort to hold Port Hudson no longer served a purpose. His men, who had been reduced to eating rats and mules, stacked their arms and gave up their works. Port Hudson, located atop high bluffs overlooking a sharp bend of the river, proved to be the ideal location for an armed fortress.

The night of the May 26, 1863 -

Our company was sent out in front to a brush fence to stay until they opened fire on us; they did not fire on us until morning. We stood all night with our guns resting on the ground, and many a man slept with his head resting on the muzzle of his gun. They opened fire on us in the morning; we went over the fence and advanced in front until we came to a piece of small woods. Here we stayed doing sharpshooting or picket duty until the charge was made in the afternoon. We were not in the charging column, but we went as far to the front as any of them in the skirmish line, and were with Duryea’s Second Zouaves, of New York. It was evening when I called the roll that night, as I was acting orderly, as First Sergeant Towle was left at Camp Parapet. I saw General Dow just before he fell saying, “Forward,men ! forward,men !”

KILLED: Lamprey was from Hampton, and Morse from Exeter. The wounded in Company I were Corps. William Dunn, of Newton, Enos Rewitzer (Miller) of Rochester, Privs. John  Mahoney and Solomon M. Newland, of Rochester, George M. Swain, J. A. Sinclair, Exeter, Albert G. Tucker and Hiram Welch, of Exeter.

Mahoney and Solomon M. Newland, of Rochester, George M. Swain, J. A. Sinclair, Exeter, Albert G. Tucker and Hiram Welch, of Exeter.

(photo: original trenches at Port Hudson)

Captain Pinkham and Lieutenant Moore were sick at Baton Rouge, and Second Lieut. John 0. Wallingford led our company and never flinched.

In one of my rambles I found a box of rebel clothing. I appropriated a shirt, so today I come out in a white shirt. It is coarse, but clean. I received from you this morning a letter dated May 9. The boys all complain of not receiving letters very often. I am afraid I shall not get another opportunity to write so long a letter as this, but I will improve every chance I have. I have filled my sheet and must close. I expect to go on special duty tonight, and I must try and get a short nap. Direct your letters the same as you have, New Orleans, and as I have said I will write whenever I have a chance. Remember me to all of my friends.”

[NOTE: Company D went in at daylight, May 27. Sergeant Hanson carried in one hundred rounds, and came out with ten. Guns got hot, had to cease firing and cool them, and swab them out with pieces of blouse torn off.]

(Photo: Miles of trenches and earthworks can still be found at the Port Hudson battlefield in Louisiana)

“Three of our batteries had taken position in our rear, and were throwing shell over us. A rebel battery opened in front, and their shells were bursting over our heads. Thinking they could not be firing at us, I looked around and saw the 165th New York coming up in column, and for a few moments we devoted all our attention to the rebel gunners as they exposed themselves in loading the guns. We fired with an intense desire that every shot might take effect. The 165th was a great deal broken when they reached the open ground, but had not lost heart. The color-bearer advanced a few rods into the open field, and they tried to form a line of battle, but the fire was too hot. Their colonel fell, with many of his men, and the line was broken.

From my position, to which I had advanced into the open field, partly screened by a friendly stump, I surveyed the field. A little squad of the 14th Maine was still standing up in the open about three rods in front of me. Our first sergeant, J. J. Hanson, was the only man I saw of our company; he was about a rod in front, shielding himself, as I was, which I considered the better part of valor. After the attack at the left of us failed, I heard a cheer at the right, where the main assault was to be made.

There was almost a continual roar from our batteries. The shells were shrieking overhead and clipping the top of the rebel works. The enemy’s batteries were active, and the air seemed  literally filled with the missiles of death. But behind the long line of rifle pits there was no sign of life. I looked again to the right and saw the long line of blue advance, with flags waving in the gentle breeze. I turned my eyes to the silent rebel rifle pits. Suddenly above them appeared a dark cloud of slouched hats and bronzed faces; the next moment a sheet of flame. I glanced again to the right; the line of blue had melted away, and down across the open field came madly plunging the war horses of Generals Dow and Sherman, wounded unto death. There was nothing more to do but wait patiently until the bugle sounded the recall and then make our way back under fire.

literally filled with the missiles of death. But behind the long line of rifle pits there was no sign of life. I looked again to the right and saw the long line of blue advance, with flags waving in the gentle breeze. I turned my eyes to the silent rebel rifle pits. Suddenly above them appeared a dark cloud of slouched hats and bronzed faces; the next moment a sheet of flame. I glanced again to the right; the line of blue had melted away, and down across the open field came madly plunging the war horses of Generals Dow and Sherman, wounded unto death. There was nothing more to do but wait patiently until the bugle sounded the recall and then make our way back under fire.

(photo: barracks for Union Soldiers at Port Hudson)

We rejoined our regiment, and when ‘night threw its sable curtain o’er the earth, we lay down in line of battle and slept the peaceful sleep that tired nature brings, while many of our comrades up under the enemy’s guns were “sleeping the sleep that knows no waking.”

June 5, Friday. Very hot again today; working on breastworks. Our artillery fire all day. Companies I, K, and D entrenching all last night and all day. Company A all last night throwing up breastworks. Rebels shell the fatigue party, but no one was hurt. Bombarding by the gunboats and artillery at night - enemy replied with grape and canister and shells.

June 5, Friday. Very hot again today; working on breastworks. Our artillery fire all day. Companies I, K, and D entrenching all last night and all day. Company A all last night throwing up breastworks. Rebels shell the fatigue party, but no one was hurt. Bombarding by the gunboats and artillery at night - enemy replied with grape and canister and shells.

(photo: Battlefield at Port Hudson)

Regiment nearly all out last night, and are out again to-day. Regiment has not had a good night’s sleep for more than a week, and are getting pretty well tired out preparing for siege guns. Worked today under fire; one man wounded by a musket ball. Byron Elliott, Company B, died of wounds at Port Hudson, Henry W. Berry, Company G, died at Carrollton.

“We threw up an earthwork for the protection of the battery; had to work in the night on account of the enemy’s sharpshooters, as they throw their shot thick and fast when they can see any of us. We worked until 6 o’clock; threw up the work so high that it protected us from the enemy’s fire somewhat. They threw one shell into the work; it burst in the earthwork, but did no damage.”

(Photos: Artist rendition of surrender at Port Hudson)

This must relate to last night and to battery 16, which is right on the battle-field of May 2 7. This great work was done under Captain Johnson and Sergt. J. J. Hanson. On the afternoon of the fourth they, under Hanson, rolled bales of cotton before them on to the spot, and went to shovelling. They first cut poles in the woods on which to carry the cotton, but found the bales too heavy to be conveyed in that manner. During the night the enemy burned a barn to light up the country, and then fired on the working party with grape and canister. The sick at Carrollton heard the firing last night. About twenty of those who were left behind sick at the Parapet came up to Port Hudson this day; they report it very dull and sickly at Carrollton, and that boys there are dying off fast.

Battery 15 is being also built by the Fifteenth men at this same time; the commencement was made in the night. A long subterranean passage leads from the rear of this battery to an underground magazine, over which an artificial hill is raised of no mean proportions when compared with nature’s own works. A battery such as was built here is a very formidable affair, and planted at South Merrimack, or even in Hollis, could easily destroy the city of Nashua.

(photo:National Cemetery, Port Hudson National Park)

(sources: all three reminiscences, taken from The History of the 15th NH Volunteer Regiment, 1862 - 1863, by Charles McGregor, published 1899;

www.exploresouthernhistory.com/porthudson; and The National Park Service, Port Hudson, LA.)