Two older Newmarket recruits, John T. Stackpole (age 35) and Jeremiah Young (age 29) traveled to Portsmouth in January 1862 and enlisted as Firemen in the US Navy Regiment. Stackpole enlisted January 21st as a 2nd Class Fireman, and Young enlisted three days earlier as a Fireman 1st Class. They were both discharged on 30 Nov 1864, and returned home to Newmarket. They were both aboard the USS Kearsarge during the Battle of Cherbourge.

USS Kearsarge, a 1550-ton Mohican class steam sloop of war, was built at the Portsmouth Navy Yard, Kittery, Maine, under the 1861 Civil War emergency shipbuilding program. She was commissioned in January 1862 and almost immediately deployed to European waters, where she spent nearly three years searching for Confederate raiders.

USS Kearsarge, a 1550-ton Mohican class steam sloop of war, was built at the Portsmouth Navy Yard, Kittery, Maine, under the 1861 Civil War emergency shipbuilding program. She was commissioned in January 1862 and almost immediately deployed to European waters, where she spent nearly three years searching for Confederate raiders.

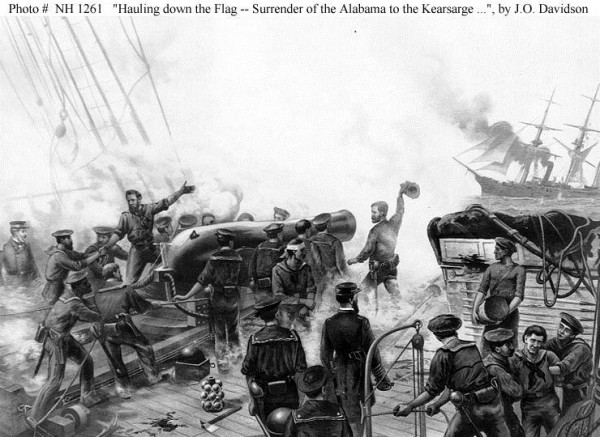

In June 1864, while under the command of Captain John Winslow, Kearsarge found CSS Alabama at Cherbourg, France, where she had gone for repairs after a devastating cruise at the expense of the United States’ merchant marine. On 19 June, the two ships, nearly equals in size and power, fought a battle off Cherbourg that became one of the Civil War’s most memorable naval actions.

In about an hour, Kearsarge’s superior gunnery completely defeated her opponent, which soon sank. Seventeen of Kearsarge’s crew received the Medal of Honor for valor during this action: The medals were awarded on 31 Dec 1864.

Kearsarge departed Portsmouth on 5 Feb 1862, for the coast of Spain sailing to Gilbralter to join the blockade of Confederate raiders. Confederate Commanding Captain Raphael Semmes was commissioned to the raider CSS Alabama on the high seas off the Azores.

From November 1862-March 1863, Kearsarge prepared for her fight with Alabama at Cadiz, searching for the raider from along the coast of Northern Europe until she was located at Cherbourg , France on 14 June 1864. Alabama had gone to port for repairs after a devastating cruise at the expense of 65 ships of the United States’ merchant marine. Kearsarge took up patrol at the harbor’s entrance to await Semmes’ next move.

19 June 1864, Alabama stood out of Cherbourg Harbor for her last action. Mindful of French neutrality, Kearsarge’s new commanding officer, Captain John Winslow, took the sloop-of-war clear of territorial waters, then turned to meet the Confederate cruiser.

Alabama was the first to open fire, while Kearsarge held her reply until she had closed to less than 1,000 yards. Steaming on opposite courses, the ships moved in seven

spiraling circles on a southwesterly course, as each commander tried to cross his opponent’s bow to deliver deadly raking fire. The battle quickly turned against Alabama due to the quality of her long-stored and deteriorated powder, fuses, and shells. Unknown at the time to Captain Semmes aboard the Confederate raider, Kearsarge had been given added

protection by chain cable triced in tiers along her port and starboard midsection abreast vital machinery.

(photo: Officers of the USS Kearsarge)

This hull armor had been installed in just three days, more than a year before, while Kearsarge was in port at the Azores. It was made using 720 feet of 1.7 inch single-link iron chain and covered hull spaces 49 feet 6 inches long by 6 feett 2 inches deep. Secured by iron dogs and eye bolts, the chain link armor concealed 1 inch deal-boards painted black to match the upper hull’s color.

This chaincladding was placed along Kearsarge’s port and starboard midsection down to the waterline, for the purpose of protecting her engines and boilers when the upper portion of the cruiser’s coal bunkers were empty.

This armor belt was hit twice during the fight: First in the starboard gangway by one of Alabama’s 32-pounder shells that cut the chain armor, denting the hull planking underneath, then again by a second 32-pounder shell that exploded and broke a link of the chain armor, tearing away a portion of the deal-board covering.

One hour after she fired her first salvo, Alabama had been reduced to a sinking wreck by Kearsarge’s powerful 11 inch Dahlgren smoothbore pivot cannons.

One hour after she fired her first salvo, Alabama had been reduced to a sinking wreck by Kearsarge’s powerful 11 inch Dahlgren smoothbore pivot cannons.

Semmes lowered his colors and sent a boat to Kearsarge with a message of surrender and an appeal for help. Kearsarge rescued the majority of Alabama’s survivors, but Semmes and 41 others were picked up by British yacht Deerhound and escaped to the United Kingdom.

(photo: painting of “The Battle of the Kearsarge and the Alabama” by Edouard Manet)

WAR ON THE KEARSARGE — Interesting Reminiscenses of Jeremiah Young

He handled the Throttle and Lever in the Famous Naval Duel; Crews of Both Vessels Fratenized After the Fight Was Over

Newmarket, N.H., Feb 17 — “Yes, I was on the Old Kearsarge,” said Jeremiah Young, who was seen by THE GLOBE correspondent at his house. ”I went on in June, 1862, and was on her until the fall of 64. I shipped at Portsmouth, NH as a machinist and run the engine in case the engineer was sick. In the contest with the Alabama I handled the throttle and reverse lever.

(photo: Emma (Sherburne) Young, Jeremiah’s wife . Famly photo courtsey Valerie Hunt Lamp)

“We had on the whole a very pleasant time. We blockaded an English frigate which we believed had been purchased by the confederacy and had been sent to France for repairs, nearly all one summer, so long in fact that they gave up sailing with her and then hitched a chain to her stern and run it to either side of the canal in which she was placed, and let her remain there.

“We blockaded the Rock of Gilbralter for a long time in search of a vessel that was reported to be the bearer of arms and ammunition for the southerners. The boat was never found, if in faqct it ever existed. We had a pleasant time off the coast of England, where we remained a long time. We were approached every 24 hours by officers of the English army, who would read the Queen’s proclamation to us which stated that no man-of-war could remain in an English harbor over that time. We would then, at the expiration of that time, take a short run up to Holland and Belgium and return.

“The boys were glad to get back for nearly every one of them had a girl among the English lasses, and most of them corresponded. Excursionists frequently came from England and France to visit us, and we certainly did not lack for girls or admiration.

An Admirable Set of Men

“The officers and men, if I do say it, were almost all of them an admirable set of men. Almost all of them had in private life a trade or profession, and their conduct on board was much the same as you would expect in any well ordered hotel.

“We had been expecting the Alabama in our direction for some days before we finally got an engagement with her. I was blackening my boots on the morning of June 18 when I was told the English boat, The Deerhound, was approaching us with the English flag flying. Shortly after the Alabama appeared. We were about five mile off the coast of Cherbourg, France.

“Capt Winslow ordered the docks cleared for action. I had charge of the throttle and reverse lever, and I could feel the vessel roll up on its side as we turned in the direction of the Alabama. I thought we were going to run into her, and I leaned forward on the lever as far as possible so as not to be thrown into the machinery when we struck; but I could feel the vessel gradually turning, and I then knew we were approaching her alongside.

“There was no apparant excitement among either the officers or the crew. I could hear every word given in command, and knew at all times just how we stood. The first shot went into the rigging. The second struck in the forward mast splintering it badly. Soon a shot penetrated the side just above the coal bunkers, right above my head an opening had been made and I expected the next shot to take my head off, so I leaned as far down as I could and began to gather up the splinters and throw them away, still hanging to the lever.

“The engagement lasted one hour and 10 minutes, and when it was over I can heartedly say I was glad. The fondest and brightest picture of a hereafter will not give me the pleasure I

experienced when I found we had captured the Alabama and its brave crew. The excitement was surpressed, but at the same time apparent. In a few minutes after the last shot the aptain piped us on deck and gave us a glass of grog.

Treatment of Prisoners

“The prisoners were quickly transferred to our vessel, and two who were wounded died on our deck. There was no quarrelling among the crew of the Kearsarge and the Alabama. A looker on would have thought we were brothers. The finest diner that the ship could provide was placed on the tables, and we all ate together.

” We had previously hung the wet clothes of the prisoners around the boiler room to dry and we had given them our clothes to wear. After the dinner grog was given to all the crew of the Alabama. The prisoners were quickly taken ashore on parole.

The Unexploded Shell

“The Kearsarge was an unarmoured vessel, and about a year before, we made iron hooks and hung big iron cables over the sides of the ship to protect her boilers. Many of these chains were broken and driven into the ship so that it was almost impossible to pull them out.

“A good deal has been said and written about the shell that was driven into the stern of the ship and did not explode, and many questions have been asked as to what damage would have resulted to us if it exploded.

(photo taken Feb 2013- Alan Knight, former US Marine, displaying the Naval Sword of his great-great grandfather Jeremiah Young)

” I do not think the damage would have been great. It would have destroyed our rudder post undoubtedly, but we had a spanker boom and we could have controlled the ship by throwing out the ship’s log and using that as a rudder. The shell was a steel shell weighing 110 pounds and struck the ship near the stern, slanting, the point toward the rudder. The percussion was imperfect, and after the engagement, we poured vinegar into the fuse and powder and rendered it useless. I understand it is now in Washington.

“The Kearsarge was struck 28 times, but not vitually. Yes, I have a pension, but not in consequence of that engagement. Before this battle, I broke a bone in the back of my hand, and I get a small pension [$3 per month]. With 15 others I received the special thanks of Congress and a medal was struck off for us. Four or five have received their medals, but I have never recieved mine. I understand that it is only a matter of negligence and some time I may get it.

“We have an organization and an annual dinner every year: we have dinners at Portsmouth, Boston, Newyburyport, and Point of Piner [ Point of Pines resort in the 1890s at Revere Beach, Massachussetts]. There are about 30 of us alive and about every year we see a vacant chair. I am 62 years old, but at the time I was aboard the old vessel I was considered very smart and active. In several little encounters I was detailed to do importrant duty where it required quickness and some little bravery. I can’t say I knew what fear was them days. I had never been injured to any extent, and I suppose I was one of the fools who run in where angels fear to tread. I don’t think of anything more of this time, but when you get ready to write the book I spoke of, come around and I shall have some other ideas for you.”

Jerry on the homefront

You would hardly think to look at “Jerry” as he is called by those who are familiar with him, that he has seen so much of life or gone through as musch as he has, though he modestly gives too little importance to his achievements. He is a very pleasant man, has a goodly share of this world’s goods and can give you the market quotations of all eastern railroad stock, and he gives it in such a way as to lead one to surmise that he has felt the certificates in his pocket and has more than enough to carry him through this world.

He moves about the town as nimble as any young man, and you may be sure that when he says a thing he means it and will not hesitate to back it up in any way necessary. All hail to “Jerry” and those of the old Kearsarge like him !————-

(Editor’s note: Seventeen of Kearsarge’s crew received the Medal of Honor for valor during this action, but despite Young’s claim to the Boston Globe reporter — he was not a receptient of this award.)

Jeremiah was born April 1832 to Nathaniel and Mary (Cram) Young in Newmarket. The Town directory of 1872 lists him as a grain dealer living in a boarding house in Creighton Street. He married Emma A. Sherburne 27 Jan 1875 in Boston. The 1880 census lists him as 48 years old, an iron machinist, married to Emma (age 39) with a son Lewis (age 5). The Jan 1883 Pension Rollsreports he received a monthly pension of $3 due to a hand injury.

Fifteen months after the Boston article appearred, Jeremiah Young committed suicide in 9 May 1895 with a gunshot wound to the head. The Newmarket Advertiser reported that he had been mentally unstable in the past to the point of confinement. At the time of his death at age 63, he had possessed quite a bit of property, but was having legal problems. His wife Emma was in the upstairs of their Elm Street home at the time of the shooting and ran for help - but he pronounced dead at the scene. He had two sons, Lewis (age 20) and Nathaniel (age 12). Jeremiah’s older brother Joseph (age 75) died three months later. Emma died 2 Feb 1942 in Portsmouth, both she and Jeremiah are buried in Riverside Cemetery in Newmarket.

Three days before Jeremiah’s suicide, former shipmate John Stackpole moved back to town from Lawrence, Mass. He and his wife took up residence on Tasker Lane, very close to the Stackpole family blacksmith shop. John and members of the G.A.R. gave Jeremiah a full military funeral and acted as pall bearers. The following month John attended the USS Kearsarge reunion held in Marblehead. John’s wife died shortly thereafter, and he moved in with his daughter’s family in Kittery, Me. He died there the first week of January, 1901. His obituary published, Wednesday Jan 9th in the Portsmouth Herald reads as follows:

OLD NAVAL FIGHTER

John T. Stackpole One of the Crew of the Old U. S S. Kearsarge.

The death of John T. Stackpole of Kittery, formerly of Hyde Park, and Lawrence, Mass., occurred at the home of his daughter, Mrs. Frank P. Whittimore on the Rogers Road on Monday night. Mr. Stackpole had the distinction of being one of the crew of the Old United State’s ship Kearsarge, at the time that the famous fighting warship sank the Alabama. He had an honorable war record.He is survived by two daughters, Mrs Frank Whittimore of Kittery and Mrs. J. P. Smith of Cambridge, Mass.. Last Sunday night he was stricken with a shock and rapidly failed afterward. The funeral will be held at the home of Mr. and Mrs. Whittimore in Kittery on Thursday afternoon and interment will take place in Lawrence. Mass. the following day. Mr. Stackpole was a member of Post No. 121. G.A.R., Hyde Park, Mass , and of the Naval Veterans of Boston.