Thomas Lees – Lt. 2nd: enlisted 24 May 1861 at age 22 as a Private in Company B, 2nd NH Infantry. He mustered in 1 Jun 1861; residence Durham, Promoted to Full Corporal 15 Nov 1861; Full Sergeant 15 Jan 1862; Full 1st Sergeant 29 Apr 1863. Listed as MIA 2 Jul 1863, he had been wounded and captured on the 2nd day of the Battle of Gettysburg and was confined at Belle Island, and Liberty, VA. Upon his release from captivity in 1863 he was promoted to Full 2nd Lieutenant on 10 Jul 1863; he later mustered out in 1864.

Thomas Lees – Lt. 2nd: enlisted 24 May 1861 at age 22 as a Private in Company B, 2nd NH Infantry. He mustered in 1 Jun 1861; residence Durham, Promoted to Full Corporal 15 Nov 1861; Full Sergeant 15 Jan 1862; Full 1st Sergeant 29 Apr 1863. Listed as MIA 2 Jul 1863, he had been wounded and captured on the 2nd day of the Battle of Gettysburg and was confined at Belle Island, and Liberty, VA. Upon his release from captivity in 1863 he was promoted to Full 2nd Lieutenant on 10 Jul 1863; he later mustered out in 1864.

Lees lived and worked in Newmarket. The 1870 Census lists him and his wife Jennie living in Newmarket, he a barber, and Jennie (age 25) without occupation. The Town directory of 1872 lists him as a hairdresser (Pavilion, Wolfeboro), owning a house on Spring Street, Newmarket. He was a Mason and a member of Rising Star Lodge of Newmarket. He was also a member of the Newmarket Post G.A.R., and his name is engraved in the Civil War monument.

“Both Thomas and Jennie were born in Ashland, England. He came to America at age 7. Enlisted Co. B, 2nd Reg. Infantry in 1861 and became a Sergeant a year later. He was captured on the 2nd day of the Battle of Gettysburg and was confined at Belle Island, and Liberty, VA. At 1863 he was promoted to Lt. and later mustered out in 1864. He moved to Wolfeboro after the war and opened a barber shop for nearly 20 years. He bought the Lake Hotel in 1891 & renamed it Hotel Sheridan after Gen. Philip Sheridan under whom he served. He died in Wolfeboro July 14, 1896 at age 54. A highly respected citizen”

(Source: Letters in the Attic: The Life & Times of Thomas Lees, from the Dead Soldier Society (Wolfeboro, N.H.)

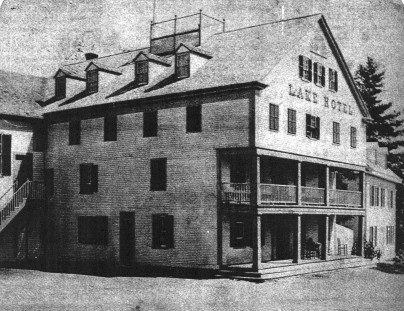

(photo: a picture of the Lake Hotel on Main Street in Wolfeboro before Lees renamed it Hotel Sheridan. The Hotel was demolished in 1941 and the spot turned into a service station. In the 1980s the Wolfeboro Marketplace was built on the property.)

(photo: a picture of the Lake Hotel on Main Street in Wolfeboro before Lees renamed it Hotel Sheridan. The Hotel was demolished in 1941 and the spot turned into a service station. In the 1980s the Wolfeboro Marketplace was built on the property.)By 1880 he and Jennie had moved to Wolfeboro. In April 1891, he purchased the Lake Hotel. At the same time he gave up his barbering trade. In May he renamed the hotel: “It is the Sheridan House now, not Lake Hotel.” Lees renamed the hotel after Philip Henry Sheridan, Civil War general.

1891, May 25: “Since Mr. Lees bought this site he has had the building repainted externally and very generally remodeled and repaired on the interior. Every room has been cleansed, painted and papered, the ceilings lightened, in fact the building has practically been rebuilt, internally. The sleeping compartments have been carpeted and fitted with all modem furnishings.

The house has also been supplied with a celebrated Beach Pond water which has already become a necessary luxury  in all domestic matters. It is the purpose of Mr. Lees to make for his new house a reputation which shall not only be a credit to himself but, as well, to the town. Everything it has intended shall be conducted strictly in conformity to the rules necessary to make it a first class year round hotel, and every attention will be bestowed upon its guests. Special endeavors will be made in the preparation of abundant wholesale food, which will be promptly served by courteous and accomplished assistants. The cuisine will be under the management of Mrs. Hoyt, which to those who have at least had the privilege of enjoying such meals as she is able to prepare, sufficient guarantee that this important department has fallen into good hands…. Lees also turned the 2nd floor of the ell into Sheridan Hall, a popular meeting hall for town and public events.

in all domestic matters. It is the purpose of Mr. Lees to make for his new house a reputation which shall not only be a credit to himself but, as well, to the town. Everything it has intended shall be conducted strictly in conformity to the rules necessary to make it a first class year round hotel, and every attention will be bestowed upon its guests. Special endeavors will be made in the preparation of abundant wholesale food, which will be promptly served by courteous and accomplished assistants. The cuisine will be under the management of Mrs. Hoyt, which to those who have at least had the privilege of enjoying such meals as she is able to prepare, sufficient guarantee that this important department has fallen into good hands…. Lees also turned the 2nd floor of the ell into Sheridan Hall, a popular meeting hall for town and public events.

1896, February 18: “Thomas Lees says, ‘The Sheridan House will be lighted by electricity before another year passes.’”

1896, May: Lees suffered a heart attack; later died. Lees was followed as proprietor by William E Wiggin who added electricity within the following year.

From the Richmond Examiner, 7/21/1863:

PRISONERS SENT NORTHWARD. – On Sunday one thousand and six of the Yankee prisoners on Belle Isle were paroled and sent to City Point, to be forwarded to the North, under the operations of the cartel of exchange.

PRISONERS SENT NORTHWARD. – On Sunday one thousand and six of the Yankee prisoners on Belle Isle were paroled and sent to City Point, to be forwarded to the North, under the operations of the cartel of exchange.

A NEGRO SOLDIER DISCOVERED. – The prison officials, while engaged in paroling the prisoners on Belle Isle, in order to send a body away by flag of truce, discovered among the enlisted men a negro, who had cropped his kinky hair short, and by the aid of a light olive complexion, and a regulation uniform, had escaped notice. He gave the name of Hascall, (intended rascal,) and said he enlisted in Massachusetts. The black sheep was removed from the white flock, and provided with quarters becoming his importance.

From the Richmond Examiner, 9/1/1863

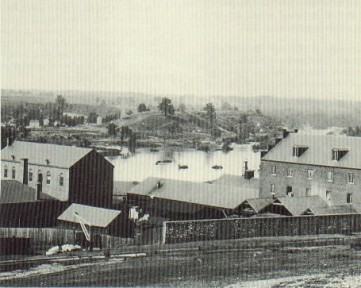

BELLE ISLE. – The camp of the Yankee prisoners now contains between 4,000 and 5,000 of them. – The camp is beautifully laid out, with streets formed by the row tents, and wells are sunk in every street. Captain Louis S. Bossieux is in command of the guard posted to guard the camp. Their quarters are on a high bluff overlooking the camp. The most rigid discipline is observed. At this season of the year a visit to the Island would be very pleasant, but military rules forbid it without a permit.

From the New York Sunday Mercury, 9/13/1863

NINTH REGIMENT, N.Y.S.M., CAMP PAROLE, ANNAPOLIS, MD., Sept. 7.

[Beginning of letter relates the author’s capture at Gettysburg and subsequent journey to Richmond.]

… The men could hardly be got along and a great many had fallen out exhausted. The guards would hallo: “You, Yanks, go along dare! get in ranks! doggon, you Yanks!” On the 17th, we reached Mt. Sidney, and on the 18th, Staunton; having marched in thirteen days 168 miles, over a turnpike, the majority of the men barefoot, no blankets, and no hats in some cases. At Staunton, they took all the India-rubber blankets from the men, and on the 19th, we took the train for Richmond, arriving there on the morning of the 20th. Daylight, they marched us to Libby – 700 of us – and kept us three hours. While here, we got a ration of bread and meat (rather small), and one of the chivalry shot a Kentucky soldier, who was deaf, in the arm – since died – for looking out of the window.

After this, they searched us; took all our money, writing-paper, haversacks, etc., allowing us only our blankets and caps. We were then marched over to Belle Island, a miserable, hot place, an acre of ground, about 4,000 men in it, and full of lice and vermin. Here we lived on ten ounces of bread and two ounces of fresh meat per day. Breakfast at 9, 10, 11 and 12 o’clock, just as it suited the Quartermaster; dinner at 3½, slop rice soup and bread. Almost two and three times a week we were turned out and counted, and put in messes of a hundred each.

On the 10th of August, they played a sharp game upon the Yanks. A citizen came over from Richmond, and offered $8 in silver for $10 greenbacks. A great many of the boys having large bills - 10’s and 20’s - got them changed; and I suppose, $500 so exchanged. The next day, the men were all turned out and searched, and the silver confiscated. On the 14th, they deliberately murdered a member of the Ninety-first Pennsylvania. He had just come in, and was sitting near the bank inside, when the guard ordered him up. He simply asked him, “Where will I go? I have no tent.” “You Yankee son of a b—-” leveling his piece, and shot him dead, wounding two others. The brute and murderer was taken before the officer in command of the post, nothing was done to him, and the Union soldier lies buried on Belle Isle unavenged.

A great deal of trading with the guard at nights was done. They seemed perfectly crazy for greenbacks, offering $10 of their money for $1 of ours; for $7 of our money would buy as

much as $10 of their money. Those that had money speculated considerable, and, I must say, a great many of our men completely robbed the boys by selling a small five cent loaf for $1; pies they would buy for twenty-five cents a-piece, they would charge $1 for; tobacco, a plug for fifty cents, worth 10 cents; and a canteen full of whiskey, $5-cost them $1! The camp had any quantity of these speculators, who would sit up all night, buy off the guards, and sell to our own men, some realizing a small fortune-one man having $1,000 in greenbacks.We were subjected to all kinds of treatment while we were in the Rebel clutches and thank God we were released from their hands on Friday, August 28, leaving Richmond at daylight, August 29, stopping two hours at Petersburg, arriving at City Point at 11, delivered upon the flag-of-truce boat City of New York. Once more under the good old flag, the Stars and Stripes, we arrived at Fortress Monroe at 4½ P.M., and reached Annapolis Sunday morning, August 31. Upon the free soil of the United States, we received our clean clothes, of which we were very much in need, got our dinner, wrote to our friends and relations, thank Almighty God for our safe deliverance to our homes and firesides. We are now in the new barracks, Camp Parole. I will drop you a line, in my next, about this place. It is under the control of Colonel [Adrian] Root, and all we want is Uncle Sam to pay us two months’ pay, give us a furlough until we get exchanged, which, by the way, is very doubtful, as the Rebels will not exchange negro soldiers. However, I hope that this will find you well, and I remain yours truly, J. F. W.

P.S. - I forgot to mention what I have seen of the inside of Rebeldom. The bogus Confederacy is nearly played out; then, provisions they have none; their large, boasted armies are all fudge. Vicksburg and Port Hudson stunned them; Charleston, Mobile, and Savannah, will kill them; and our Government ought and can take Richmond any day, if they have a mind to; no soldiers around there nearer Fredericksburg. The city militia does not amount to anything, and the people of Richmond will help us as soon as our forces near the city. J. F. W. written by John F White, Jr., age 28, enlisted in the 9th New York State Militia (83rd N. Y. Infantry). He was promoted to corporal on Oct. 21, 1863 and served until his discharge on Jan. 10, 1865. In 1867, he enlisted in the 31st U. S Infantry and was discharged at Fort Stevenson, Dakota Territory in 1870. He died in Kansas City on February 8, 1902.)

(Source: From Writing & Fighting the Civil War : Soldier Correspondence to the New York Sunday Mercury, by William B. Styple, et al., 2000.)

From the National Tribune, 9/3/1903

TO CAPTIVITY LED Results of a Daring Enterprise.

EDITOR NATIONAL TRIBUNE: [author relates in a lengthy paragraph his capture on July 5, 1863 at Greencastle, Pa., and subsequent journey to Richmond - not transcribed]

…After a brief stay at Libby Prison, we were transferred to Belle Isle, where Lieut. Boisseux was in charge. On the second day there we were relieved of all valuables, money and watches especially. I had a few dollars in my pocket book, which I threw back over the dead line, at the same time calling Lieut. Boisseux a thief. Infuriated, he seized a gun and would have run the bayonet through me had not one of the guards interfered in my behalf. However, he gave me a violent kick and ordered me to go after the pocket book. Instead of going, I called to the boys on the other side to throw it over to me, which they did. When the Lieutenant found there was little wealth in the pocket book he was evidently disappointed, plainly showing that he was disgusted with me for not having a more plethoric wallet.

However, when he ordered a thorough investigation of my scant habiliments the money I had sewed up in my pants was revealed to his rapacious gaze, and, of course, he eagerly took it all.

The prisoners were permitted to bathe in the James River, and Lieut. Boisseux, treating me with distinguished consideration, put me in charge of the detachments of bathers, my compensation being extra rations. He ordered me to not let more than 40 go into the water at one time. Again perversely insubordinate, I let out from 75 to 80, and gradually increased the number to 150. After two weeks duty at the “bathing resort,” Boisseux, probably afraid I would take the entire encampment “in a-swimming,” transferred me to the Commissary Department. My duty was to go on the boat to Richmond for bread, a ration of which was about enough for a two-year-old child to eat at one meal. In addition to the bread, a little bean soup was served - one or two beans in a cup of liquid, that represented a dead horse or mule.

My sojourn at Belle Isle was in July and August. When a detachment of prisoners went out, Aug. 25, 1863, Lieut. Boisseux told me to accompany them, although my name was not on the list for exchange. He sent me along as an “extra,” because he had insulted me, and I had had the courage to defend myself.

I well remember the “red-headed Sergeant at the gate.” I think he was killed when our troops entered Richmond - written by JOHN CLEMENS, Co. L, 1st N. Y. (Lincoln Cavalry), Canton, Ohio.