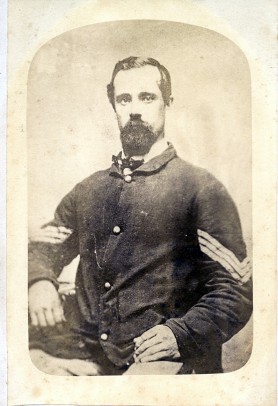

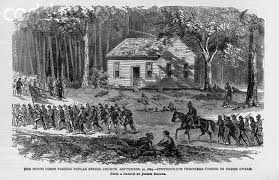

enlisted from Newmarket on 21 Oct 1861 as a Corporal in Company C, 6th NH Infantry. He mustered in on 27 Nov 1861, and was promoted to Full Sergeant. Captured 30 Sep 1864 during the Battle at Poplar Springs Church, he was taken to Salisbury Prison, N.C. where he (like so many others) died on 23 Dec 1864 of disease and starvation.

Charles was born in the Barrington or Durham on 23 Aug 1836 to Henry (b.1818, d.1892) and Susan (Rundlett) Willey (b.1816, d.1864). He was working as a stonecutter in 1860. and living with his wife Mary and children in Newmarket. He married Mary Caroline Twombly in Newmarket on 28 Jun 1853; Mary was born 1836 in Durham; and died 1915 at her daughter’s home in Exeter. She was the daughter of stone mason Samuel Towmbly (b.1805; d. 1865) and he wife Susan (Durgin) Twombly (b. 1805; d. 1876).

The Newmarket Town Treasuer’s Report of 1864 lists Mary as one of several people who loaned the Town money that year. There was still great support for the soldiers and their families. There was also a great fear that the Town would be bankrupt because it was having considerable difficultly staying financially solvent. The State was in arrears in paying back its promised share of soldiers’ bounties and fees. Mary gave a promissory note of $200 while her husband was imprisoned, and she was caring for five children.

Family lore tells that during the war, Charles Henry was granted a leave and he walked home to NH to visit his family. Along the way, he found a pistol used by a Confederate soldier which he picked up and carried home with him. After returning to duty, he was captured and died in a Southern Prison Camp in NC. The pistol was passed through the family to Richard S. Willey.

Besides his wife Mary, Charles left behind five children: Alburn Leroy Willey (1856-1917) ; Gracey Willey (1856 -); Clara “Carrie” Willey (1858-1938); Kate Willey (1862 -1948); and Georgianna Willey (1864 – 1942) The 1870 Census shows Mary and her daughter Grace G, (age 13) and her son Leroy (age 16) all working in the cotton mills. And by 1890 she was still living in town and receiving a widow’s pension. Mary died 26 Mar 1915 in Exeter; and is buried in Newmarket. [ for extended familly history, see Willey Geneaology on Historical Society website]

The Rebels captured another Newmarket-connected man at the same Battle at Poplar Springs on 30 Sep 1864.

Sergant was engaged in the same fight, but assigned to Company C, 11th Infantry. Charles was initially born in Newmarket; however the 18 year old had since moved away. He enlisted and  mustered in the same day on 16 Jan 1864 from Jaffrey, NH. with the rank of Private. He was wounded 30 July 1864 in a mine explosion at Petersburg, VA. He had recovered enough to fight again at Poplar Springs when he was captured. The young teenager lived merely another three weeks before he died 23 Oct 1864 in the infamous Salisbury, N.C. prison.

mustered in the same day on 16 Jan 1864 from Jaffrey, NH. with the rank of Private. He was wounded 30 July 1864 in a mine explosion at Petersburg, VA. He had recovered enough to fight again at Poplar Springs when he was captured. The young teenager lived merely another three weeks before he died 23 Oct 1864 in the infamous Salisbury, N.C. prison.

Salisbury Prison was the only Confederate Prison located in North Carolina. Located in Salisbury, on 16 acres purchased by the Confederate Government November 2, 1861, the prison consisted of an old cotton factory building measuring 90 x 50 feet, six brick tenements, a large house, a smith shop and a few other small buildings. When Gov. Henry T. Clark of North Carolina shopped for a new prison camp, the abandoned cotton factory in downtown Salisbury seemed like a good deal. It was on a rail line, facilitating prisoner movement, and the brick factory and accompanying wooden boarding houses were deemed sufficient for the anticipated 2,000 inmates. Wells provided fresh water, and the local countryside was rich in produce, making provisioning easy.

Most important, the price was right. The factory’s owner wanted only $15,000 for the 11 acres, which included $500 worth of machinery. He was also willing to accept payment in Confederate bonds. And while $2,000 was needed for iron bars and other security measures, Clark was assured that the prison could be resold after the war for $50,000, a tidy profit. So on November 2, 1861, the complex was purchased.

Most important, the price was right. The factory’s owner wanted only $15,000 for the 11 acres, which included $500 worth of machinery. He was also willing to accept payment in Confederate bonds. And while $2,000 was needed for iron bars and other security measures, Clark was assured that the prison could be resold after the war for $50,000, a tidy profit. So on November 2, 1861, the complex was purchased.

Surrounded by a simple board fence, Salisbury Prison promised to be a comfortable detention center for deserters, spies, and Southern citizens suspected of disloyalty. Mid-December 1861 brought the first Union prisoners, and by March 1862 Salisbury housed a total of 1,500 prisoners. Conditions were good until late 1863. Food and room were plentiful, and the prisoners even formed baseball teams. Only one death was reported.

As the Union army advanced, more and more Northern prisoners were transferred to Salisbury from occupied territories. The prison’s capacity of 2,000 was reached early in 1864. By October 1864, over 10,000 men were crowded into tents, mud huts, and even holes in the ground, as the prison buildings were increasingly used as hospitals.

The Confederate government couldn’t afford the bills. Salisbury’s acreage became a quagmire, with no stream running through the camp to carry away waste, sanitation was a

nightmare, and the wells became fouled.

Many Union soldiers were captured at the first battle of Bull Run at Manassas. It was these soldiers who became the first prisoners at Salisbury. Southern political prisoners, along with deserters from both sides joined the swelling ranks of prisoners inside the walls of Salisbury Civil War Prison.

Paroles and prisoner exchanges came almost to a complete halt and Salisbury Prison became extremely overcrowded. Rations and supplies were depleted. Conditions worsened, disease and fever ran rampant and spread easily among the prisoners who had become weakened due to malnutrition. Many prisoners suffered and died. They were buried in 18 trenches which are 240 feet long. Estimates place the number in the trenches at 11,700¹ and the individual graves of another 412 prisoners of which 283 are unknown. Today, there are thousands of grave markers lined up row after row.

Baseball was played at Salisbury in the early part of 1862 when POWs from New Orleans and Tuscaloosa were sent to Salisbury. W.C. Bates mentioned the advent of Baseball at Salisbury in his Stars and Stripes but regretted “that we have no official report of the match-game of baseball played in Salisbury between the New Orleans and Tuscaloosa boys, resulting in the triumph of the latter; the cells of the Parish Prison were unfavorable to the development of the skill of the ‘New Orleans nine.’ “¹ Prisoner Gray mentions that baseball was played nearly every day the weather permitted. Claims have been made that these were the first baseball games played in the South.

The most ambitious escape attempt took place on Friday, November 25, 1864. Owing to lack of food, very little shelter, the extreme winter of 1864 and overcrowding due to transfers from Andersonville — the prisoners rushed the gates. The gate cannon was fired three times killing 65 persons outright and wounding and unknown number. Official reports put the number of prisoners who died from wounds and cannon fire at over 250.

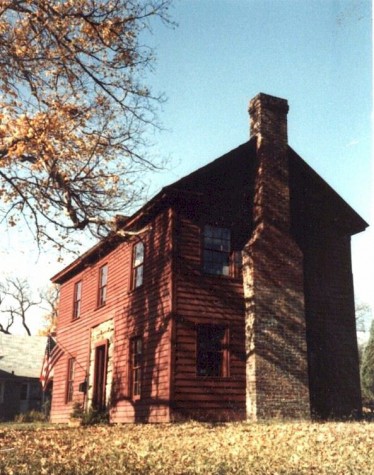

(Photo: This is the only structure that remains from the Confederate Prison. It is located in the 200 block of East Bank Street, Salisbury).

(Photo: This is the only structure that remains from the Confederate Prison. It is located in the 200 block of East Bank Street, Salisbury).Salisbury Prison saw a succession of nine commandants, most notable of which was Maj. John Henry Gee of Florida. In 1866, Gee was tried for war crimes in Raleigh and was acquitted. That stood in contrast to Capt. Henry Wirz of Anderson, the only other prison camp commander tried for war crimes. Wirz was convicted and hanged.

By early 1865, the war was all but over and remaining prisoners at Salisbury were readied for exchange or liberation. A group of about 3,700 prisoners were marched to Greensboro, where they were transported by train to Wilmington for the journey north. Other, sicker prisoners were sent to Richmond. N one was left at the prison camp April 12, when Union General Stoneman arrived to free the prisoners.

He ordered the prison burned; today only a few bricks remain in private collections.